On Wednesday May 20 I went on a tour of the Hanford Site. This is a decommissioned nuclear reactor on the Columbia River in south-central Washington which had the sole mission of creating plutonium for weapons. The B Reactor there was the first large scale reactor built for this purpose; it was created for the Manhattan Project based on Fermi’s prototype at the University of Chicago.

I did this as a part of a tour offered by the Department of Energy. As I understand, there were 1500 spaces for the tour offered for free on a date advertised on the website. On the registration date I reserved my spaces at 6am, at which time several hundred spaces had been taken already. Out of curiosity I checked registration from work around 9am on that day; the spaces were all filled by then. Our five-hour tour started at 7:30am. We queued to be sniffed by a bomb dog at that time and were on the bus and gone by 7:35. There were a few reserved seats unclaimed on our bus; I wonder if anyone traveled all the way out to that desert, was a bit late that morning, and then missed their chance?

The facility is spread over 1500 sq km; in comparison Seattle is on 140 sq km. Despite that, it did not seem to take long to travel between the desolate building complexes within the compound, and the tour guide talked continually during the ride. Everyone spoke starting with the assumption that all present already knew quite a bit about the site, nuclear physics, and pollution. It suited me but as no one else ever asked questions to the speakers, I wondered if they were getting what they expected.

The first stop was with a researcher who was cleaning the aquifer throughout the site so as not to allow the hexavalent chromium which was used as a rust-proofing agent in the reactor continue to seep into the river. Since all the underground water flows toward the river, the strategy for cleanup is to drill wells before the river as a sort of barrier. They clean the water they extract and then dump it higher in the aquifer so that the same water flows toward that same well, hopefully becoming cleaning each time it cycles. They use column chromatography to clean the water first by running sequentially through four vats; the first tank collects most of the pollution, then the second more, and by the time it gets through the four one the hexavalent chromium is at some level they like. They said that the federal government sets some maximum allowable prevalence for this compound, and that the state has some stricter requirement, and the EPA has some even stricter standard, and their own capability can push levels lower than that, assuming they run long enough. This system is becomes more effect as more water is processed more quickly. The researcher said that by some standards this water cleanup has become more costly than the cost of the plutonium production, but what else can be done with what the last generation gave to us? The consequence of the pollution so far has been disruption of the wetlands around and life in the river.

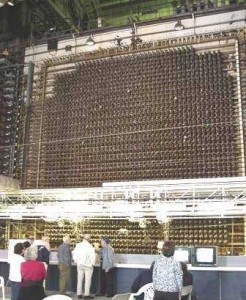

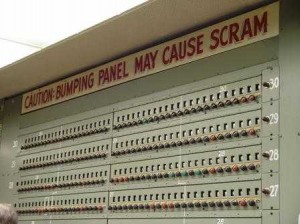

Next we went to the B Reactor. I find it difficult to critique industrial architecture but to me it seemed like a nondescript smallish factory with an exhaust tower from the outside. The guides said that we were restricted to being in the place for a limited amount of time due to radiation, and that the interior has all been shellacked several times to contain any radioactive dust. I cannot support or refute any estimate of danger of being in the B Reactor, but I had no concern about visiting nor did anyone else voice one. The graphite cube containing slots into which uranium rods could be inserted was emotion-inducing. It looked alien to me because I could get so close to it, could see that so much of it needed to be tended by hand, and yet could recognize that what was done then would today be done with computers. The picture shows some of the knobs in the main control room. There were several variables, like temperature and pressure, which needed to be constantly monitored in the core. Since computers did not exist when this device was operational, all of these readings had to be monitored by human biological capability. There were levers, buttons, cranks, robotic pens that drew lines on graphs, and wire switchboards that connected thousands of data generators to individual input devices. I gathered that someone had to plug each of the thousands of gauges into some printer, individually, and then note the readout. All of this must have required complicated human management, and surely the people assigned the rote duty of monitoring these devices for years must have been brilliant physicists, because who else could have taken such a shallow and boring job seriously? I think anyone reading this post would immediately discern that all this complicated work could be simply managed by the computer in a contemporary cell phone. The picture mentions “SCRAM.”

This has nothing to do with anyone running away from the reactor; the guide said this is an acronym for “Safety Control Rod Axe Man.” If something goes wrong with the reactor, then a man who sits in a chair holding an axe would chop some rope, thus dropping some nickel rods into the reactor in order to absorb neutrons and stop the reaction. I wonder if that man was also a physicist? Who else could be trusted to respect such a job?We went to a sort of landfill after that. It was large enough to contain entire buildings, and in fact it did. This landfill was designated only for Hanford nuclear waste. Looking at the immense size of it gave me the feeling that I could not easily understand the scope of the Hanford problem. I must say that all the workers to whom our guide introduced us were very forward with information about their work. We actually saw bulldozers compressing junk into a section of the landfill. The worker said that soon the tractor would be retired despite it, as a piece of machinery, still being fully operational. Its just that over time it becomes radioactive and it is less expensive to drive the tractor into the landfill and leave it than it would be to wash it. The whole landfill is lined with thick cement, thick plastic, and other materials. It is designed to be water and dust proof and to not crack, and eventually to have an enormous lid put over it. Until the lid is put over it, which should happen in about ten years when it is finally filled, they have to pump rain out of it because water takes up too much space. This water is concentrated; the polluted water goes back into the landfill and the cleaner water goes into the ground.

The last part of the tour was to drive around some of the factories. There is not much urban development around Hanford so it is necessary to have construction facilities for their private use. They have concrete and glass factories on site because a lot of the things in the landfill need to be encased in either concrete or glass. There are also huge storehouses for construction materials, like metals, wires, plastics, chemicals, and all the other materials one would need to manufacture a city.

I have never taken such an overtly information-packed tour marketed to the general public, and I might even say that with it being intense for the entire five hours and having no breaks except at the expense of missing something, there cannot even be many such tours in existence. It was a wholly satisfying experience for me to take this tour and I would recommend it to anyone with an interest in the related issues.